“To me, bad taste is what entertainment is all about. If someone vomits watching one of my films, it's like getting a standing ovation. But one must remember that there is such a thing as good bad taste and bad bad taste. It's easy to disgust someone; I could make a ninety-minute film of people getting their limbs hacked off, but this would only be bad bad taste and not very stylish or original. To understand bad taste one must have very good taste. Good bad taste can be creatively nauseating but must, at the same time, appeal to the especially twisted sense of humor, which is anything but universal. (Waters 2)

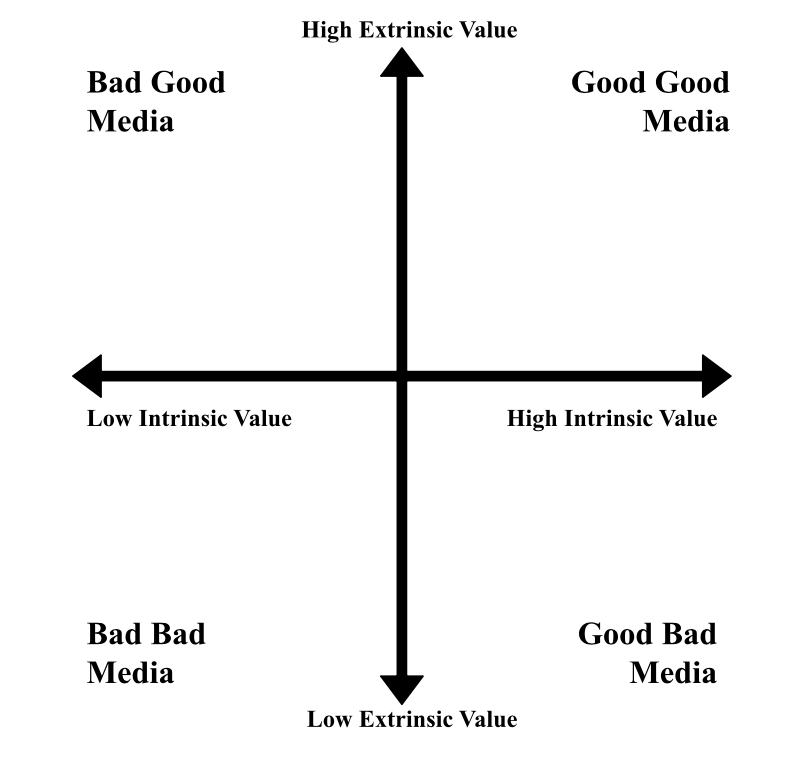

Cult filmmaker John Waters examines a core tenant of his own creative philosophy in this excerpt of his 2005 memoir, Shock Value. Framing what is understood as horrendous in an artistic, valuable semblance may seem paradoxical, but this is what Waters has built his career off of. Poverty, violence, nudity, drug abuse, mental illness, and bodily fluids are prominent staples of his filmography, not as topics of shame, but almost as though they are subjects of worship. However, Waters clearly indicates there is a proper means of handling these subjects, through the study of “good bad taste,” and the potential dangers of “bad bad taste.” Beyond the simple wordplay exists a deeper underlying framework to consider within all forms of media. Within the phrase “good bad taste” lies a dichotomy of value between the former “good” and the latter “bad,” particularly with Waters’ films in mind. What makes Waters’ taste good is its intrinsic quality — what makes it “anything but universal.” Waters’ bad taste, or what he seems to lack interest in achieving, is a wider interpretation of its value, its cultural utility. These unique combinations of taste and its associated media can be thought of as a pair of intersecting axes, a model that visualizes both the intrinsic and extrinsic values of media.

Fig. 1. The Waters Graph.

What Waters also communicates through his filmmaking is the ability to transcode concepts from one quadrant to another. “Bad bad” media, that which has no clear intrinsic or extrinsic value, can be framed in a different light and consequently get reinterpreted by viewers. One example of this in the realm of fine art is Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. The uninstalled urinal that makes up the readymade has little to no extrinsic appeal, as it is relatively worthless as a commodity in its current state. From the perspective of intrinsic value, a urinal will rarely denote something of importance to oneself. Regardless of the personal connections one may have had with urinals in the past, the punctum of the object likely draws out a sense of neutrality or potentially disgust from the individual. However, Duchamp has not left this object in a vacuum; the object has been presented as art, and this shifts the relation the individual may have with the object. The deliberate uselessness of the object now makes the viewer question the function of the piece, and the function of art as a whole. In the process of staging the readymade, from a mundane object to an interpretable piece of art, the creation of Fountain functionally transforms “bad bad” media into “good bad” media. Perhaps the current notoriety and historical impact of Fountain has provided it a form of extrinsic utility, that of a tool for analysis in art, philosophy, and visual culture, making it fundamentally “good good” media within this framework.

Fig. 2. Fountain, readymade by Marcel Duchamp. Image from SF MOMA.

With Waters and Duchamp, the interest in subverting hegemonic attitudes around what is deemed as worthless or vile is explored through film and fine art respectively, but designer and performance artist Leigh Bowery uses the medium of theater for this effect. Bowery was known for his form-warping fashion design that emphasized parts of the body that were socially shunned, such as the buttocks, the stomach, and the feet. This work was often colorful, textural, crude, and fetishistic in itself, but what entirely amplified Bowery’s vision were his live performances. A pivotal moment in Bowery’s career took place a year before his death in 1994, his performance at the annual Wigstock drag festival. In this piece, Bowery’s unique utilization of indecorous symbols demonstrates how theater can be used as a counter-hegemonic tool by transcoding the intrinsic value of taboo subjects.

The PerformanceThe subject of “bad bad” media within the performance was crafted by Bowery himself using the theatrical warping of what could be deemed as “good good” media. Formal elements usually included to engage and immerse the audience are instead used as an opportunity to repulse and confuse them. In a recording of the performance, Bowery’s introduction to the stage mentions a previous performance, where he “saw it fit to spray the audience with an enema,” prompting vocal fear and disgust within the crowd (Lafreniere 0:00:20). This negative prefacing is followed by a performance that seems tame in comparison, with Bowery simply dancing around stage in his elaborate costume while singing The Beatles’ “All You Need is Love.” At the climax of the song, Bowery promptly lays on a table, and a nude woman coated in a dark substance breaks open the crotch of his tights and crawls out of his costume. After chewing off a fake umbilical cord, he takes a bow at the front of the stage with the woman, proclaiming her as “the first baby born at Wigstock” (0:04:05). This pseudo-birthing wholly subverts the image of childbirth in prevalent culture as a beautiful miracle, as the common idea of the infant as a cherub or Christ-like symbol is shattered. Bowery’s depiction of the baby is coated in a thick layer of biofilm, with a cold stare that attributes an amount of sentience rarely associated with the first moments of life. The presence of secondary sexual characteristics on the figure actuates a distinct cultural anxiety around nudity and applies it to the exceptionary subject of an infant. Bowery’s baby is more comparable to a parasitic stranger that just emerged from the body, a darker, more alienated view of childbirth. In the portrayal of the mother, the costume Bowery wears also adds to the alienation of the subject of childbirth. The modesty and garish patterns on the larger, matronly silhouette creates a hyperbolized depiction of a mother, but the masked appearance denies the spectator any real sense of familiarity with this character.

There is also a wider sense of religious allegory when this piece is compared to the Madonna and the Christ Child of our cultural zeitgeist. Bowery stands in complete antithesis with the framing of gender roles, as the man becomes the bearer of life, and the woman manifests as the miraculous creation. The naturalism of prevalent depictions of the Madonna are also flipped with the crude, theatrical framing of the entire event. These factors, along with dispelling the purity and innocence symbolized both in the mother and child, Bowery’s performance can be viewed as a celebratory birthing of an Antichrist figure. In his book On Ugliness, Umberto Eco observes how as the cultural vision of the devil was neutralized, his prior traits were adapted to portray common enemies; the “other groups” of society “took the place of Satan” in appearance (185). The Antichrist, “the first enemy Christianity found itself up against,” became a supplemental figure, and users of this image “insist[ed] on his obscene ugliness.” The adaptation of this archetype is another stigmatic element Bowery has reappropriated to change thought around.

With these approaches to presenting media that lack value from an intrinsic and extrinsic perspective, Bowery’s added value to these subjects can now be understood. The usage of “All You Need is Love” as a backing song provides a sharp juxtaposition between the Beatles’ hit and the rest of Bowery’s performance. The song itself has been widely recognized as a “fairly straight forward and commercial song” with the simple message of spreading love (Jones et al.). It has been widely accepted in culture as a piece of “good good” media, which serves to better the individual and humanity as a whole. What Bowery does by using it is challenge a culture that openly embraces a message of radical love by presenting something that would be widely contentious and disapproved of. It tests the principles of the song, demanding that even something horrific and strange in appearance must be approached with support and open-mindedness. Within the content of the performance itself, Bowery lovingly welcomes an Antichrist figure into the world, showing a form of total acceptance that even his direct audience struggles to engage with.

By focusing more on sensation and spectacle, Bowery’s larger abstract vision impels a wider sense of meaninglessness on convention. With the lack of clear narrative and its shocking nature, Bowery’s piece echoes Antonin Artuad’s theory of the Theater of Cruelty. Artaud’s philosophies often echoed the work of writers and artists like Duchamp, even working directly alongside other surrealists in the 1920s for a brief period (Wetherington). As the surrealists embraced Marxist ideologies, theater was soon considered an intrinsically bourgeois medium. Artaud refused to dismiss theater, but instead sought to replace current practices, and the Theater of Cruelty was his solution. In The Theatre and Its Double, Artaud claims that contemporary theater has been reduced to serving as a means of escapism, and it had unaccustomed viewers to the “immediate and violent action that theater should possess” (84). Ideally, theater should target the senses and “attack the spectator’s sensibility on all sides,” break the separation between the house and the stage, and resuscitate an idea of “total spectacle” (86). Artaud proposes a vision of theater full of danger and uncertainty in order to expose and undermine the conventions of society, and this is fundamentally something that Bowery utilizes as well. There’s something essentially anti-immersive to this piece. It is the glorious staging of something perceivably lacking any sense of utility, and this in itself provides a sense of intrinsic value to the viewer by questioning how the utility of anything is deemed.

Theater has been shown as an essential medium for the reevaluation of taboo subjects, and even within other mediums, theatricality has been a common basis. Waters’ films would not have flourished without the humorous hyperbolized flair he depicts his transgressive subjects with, and Duchamp’s Fountain couldn’t have worked without the literal staging of the urinal to identify it as art. In some ways, these artists that built the precedent for “good bad” media have become powerful assets in contemporary culture, a full circle back into “good good” media. Eco encapsulates how these perceptions around ugly media evolve: “What will be appreciated tomorrow as great art could seem distasteful today,” and “taste lags behind when new things come along” (366). Perhaps it’s the ugly media itself, like Bowery’s performance, that evolves and propels the tastes and values of the world towards the future.

Works Cited

Antonin Artaud. The Theatre and Its Double. Translated by Mary Caroline Richards, New York, Grove Press, Inc, 1958.

Jones, Max, et al. “Latest Message from the Beatles Is “Love.”” Melody Maker, 8 July 1967, p. 13, www.worldradiohistory.com/UK/Melody-Maker/60s/67/Melody-Maker-1967-0708.pdf.

Steve Lafreniere. “Leigh Bowery Performs at Wigstock 1993.” YouTube, 7 Nov. 2007, www.youtube.com/watch?v=0VWV1vsHnJc. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

Umberto Eco. On Ugliness. Random House, 2007.

Wetherington, Laura. “Artaud and the Surrealists.” Jacket2.org, Jacket2, 2013, jacket2.org/commentary/artaud-and-surrealists.